VLADIMIR MAYAKOVSKI

POETA RUSSO, DESIGNER GRÁFICO, MILITANTE CULTURAL FUTURISTA E POLÍTICO, HOMEM SÓ CORAÇÃO - 1893-1930.

Museu Maiakovski, praça da Lubianka, Moscou.

Nasceu em Baghdati, Império Russo, em 19 de

julho de 1893.

Faleceu (suicídio)

em Moscou, Rússia,

União Soviética, em 14 de abril de 1930.

Museu Maiakovski, praça da Lubianka, Moscou.

Vladimir

Mayakovski

Fonte: Blog Pensador

http://pensador.uol.com.br/autor/vladimir_maiakovski/biografia/

Vladimir Mayakovsky nasceu na Geórgia, então Rússia, em 1893.

Entrou para a facção bolchevique do Partido Social-Democrático

Operário Russo ainda na adolescência, sendo preso várias vezes.

Junto com David Burlyuk, Khlebnikov e Kruchonykh, publica o

manifesto cubo-futurista intitulado Uma bofetada no gosto do público.

Após a Revolução de Outubro 1917, trabalhou na Agência Telegráfica

Russa, foi redator da revista LEF (de Liévi Front, Frente de Esquerda),

escreveu teatro, fez inúmeras viagens pelo país, aparecendo diante de vastos

auditórios para os quais lia os seus versos.

Nuvem de calças, publicado em 1915, foi talvez o seu primeiro grande

poema a ser editado. Suicidou-se com um tiro, aos quase 37 anos de idade, em 14

de Abril de 1930.

Vladimir Mayakovski [1893 – 1930]

Nasceu em Baghdati, em 19 de julho de 1893;

faleceu (suicídio) em Moscou, em 14 de abril de 1930

Origem: Wikipédia, a enciclopédia

livre.

Vladimir

Maiakovski

|

|

Mayakovsky 1929 a.jpg / Mayakovsky

em 1929

|

|

Data de

nascimento

|

19 de julho de 1893

|

Local de

nascimento

|

|

Nacionalidade

|

|

Data de

morte

|

14 de

abril de 1930 (36 anos)

|

Local de

morte

|

|

Gênero(s)

|

|

Pseudónimo(s)

|

Vladimir

Mayakovsky

|

Cidadania

|

|

Período de

atividade

|

1912—1930

|

Influenciados

|

|

Vladimir Mayakovsky (em russo: Владимир Владимирович Маяковский; nasceu em Baghdati, Império Russo, 19 de julho de 1893; faleceu em Moscou, Rússia, 14 de abril de 1930. Também chamado

de "o poeta da Revolução",

foi um poeta, dramaturgo e teórico russo, frequentemente

citado como um dos maiores poetas do século XX, ao lado deEzra Pound e T.S. Eliot, bem como "o maior poeta do futurismo". [2] [3]

Biografia

Vladimir Vladimirovitch Mayakovsky

nasceu e passou a infância na aldeia de Baghdati, nos arredores de Kutaíssi, na Geórgia, Império Russo. [4] [5] Lá

cursou o ginásio e, após a morte súbita do pai, a família ficou na miséria e

transferiu-se para Moscou, onde Vladimir continuou seus

estudos. [4]

Fortemente impressionado pelo movimento

revolucionário russo e impregnado desde cedo de obras socialistas, ingressou

aos quinze anos na facção bolchevique do Partido Social-Democrático Operário

Russo. Detido em duas ocasiões, foi solto por falta de provas, mas em 1909-1910

passou onze meses na prisão. Entrou na Escola de Belas Artes, onde se encontrou

com David Burliuk, que foi o grande incentivador de sua iniciação poética. Os

dois amigos fizeram parte do grupo fundador do assim chamado cubo-futurismo russo, ao lado de Khlebnikov, Kamiênski e outros. [6] Foram

expulsos da Escola de Belas Artes. Procurando difundir suas concepções

artísticas, realizaram viagens pela Rússia.

Após a Revolução de

Outubro, todo o grupo manifestou sua adesão ao novo regime. Durante

a Guerra Civil, Mayakovsky se dedicou a desenhos e legendas para cartazes de

propaganda e, no início da consolidação do novo Estado, exaltou campanhas

sanitárias, fez publicidade de produtos diversos, etc. Fundou em 1923 a revista

LEF (de Liévi Front,

Frente de Esquerda), que reuniu a “esquerda das artes”, isto é, os escritores e

artistas que pretendiam aliar a forma revolucionária a um conteúdo de renovação

social. [4]

Fez numerosas viagens pelo país, aparecendo

diante de vastos auditórios para os quais lia os seus versos. Viajou também

pela Europa Ocidental, México e Estados Unidos. Entrou frequentemente em

choque com os "burocratas" e com os que pretendiam reduzir a poesia a

fórmulas simplistas. Foi homem de grandes paixões, arrebatado e lírico, épico e

satírico ao mesmo tempo. Era fanático pela equipe de futebol Spartak Moscou. [carece de

fontes]

Oficialmente, suicidou-se com um tiro em

1930, sem que isto tivesse relação alguma com sua atividade literária e social. [7] [8] [9] Tal

fato tem sido questionado, pois na época o poeta estaria sendo pressionado

pelos programas oficiais que desejavam instaurar uma literatura simplista e

dita realista, dirigidos por MViatcheslav

Molotov, que teria perseguido antigos poetas revolucionários como

Maiakovski. [4] [10] Em vista disso, aponta-se a

possibilidade real de um suicídio forjado por motivos políticos. [11] [7]

Obra

Lápide de Vladimir Majakovski em Moscou (no cemitério

Nowodewitsche)

Sua obra, profundamente revolucionária

na forma e nas idéias que defendeu, apresenta-se coerente, original, veemente,

una. A linguagem que emprega é a do dia a dia, sem nenhuma consideração pela

divisão em temas e vocábulos “poéticos” e “não-poéticos”, a par de uma

constante elaboração, que vai desde a invenção vocabular até o inusitado arrojo

das rimas. [4] [5]

Fazendo parte do grupo

"Hylaea", que daria origem ao chamado cubo-futurismo, seu primeiro livro de

poemas, no entanto, seria de estética influenciada pelo simbolismo, e nunca chegaria a público,

tendo sido escrito quando o poeta estava na prisão e apreendido pela polícia no

momento da sua libertação. [12] [13]

Aproximando-se de David Burliuk na década de 1910, passa a escrever em

um estilo aproximado do cubismo e

do futurismo, influenciado pelo primitivismo eslavista e pelalinguagem

transracional de Velimir Khlebnikov e outros, repleto de imagística urbana

e surpreendente, com um certo ar impressionista e, ainda, simbolista. Esta fase de sua

poesia é a mais apreciada por poetas como Boris Pasternak, em função de ainda manter

alguns recursos simbolistas e métrica rigorosa em alguns poemas. [4] [5]

Em seguida, já na década de 1920, sua

poesia, apesar de haver uma continuidade no que diz respeiro à inovação

rítmica, à rimas inusitadas, ao uso da fala cotidiana e mesmo de imagens

inusitadas, assume um tom direto. [14]

Ao mesmo tempo, o gosto pelo

desmesurado, o hiperbólico, alia-se em sua poesia desta época à dimensão

crítico-satírica. Criou longos poemas e quadras e dísticos que se gravam na

memória. Traduções sem preocupação com a forma dos poemas produzidos nesta

época têm dado ao público uma imagem errônea do poeta, fazendo-o parecer um

"gritador". [14]

Na realidade, era um poeta rigoroso, que

chegava a reescrever sessenta vezes o mesmo verso e recolhia muito material

informativo e linguístico para posterior uso nos seus poemas. Criou também

ensaios sobre a arte poética e artigos curtos de jornal; peças de forte sentido

social e rápidas cenas sobre assuntos do dia; roteiros de cinema arrojados e

fantasiosos e breves filmes de propaganda. [14]

Tem exercido influência profunda em todo

o desenvolvimento da poesia russa moderna, bem como sobre outros poetas e

movimentos no mundo inteiro, como Hamid

Olimjon, Nazım Hikmet, Hedwig

Gorski, Vasko Popa e Caetano Veloso [1] .

Referências

1.

↑ Ir para:a b Zcastel. O amor de

Maiakóvski…, de Gal, e de Caetano!. Visitado em 04 de janeiro de 2013.

3.

Ir para cima↑ Karpinski, Joanne B.. Poetics and Polemics: Strategies of Ezra Pound and Vladimir

Mayakovsky (em inglês).Colorado: University of Colorado at Boulder,

1980. 572 p. OCLC 7647562 Página visitada em 04 de janeiro de 2013.

4.

↑ Ir para:a b c d e f v-mayakovsky.com. Vladimir

V. Mayakovsky (em rússo). Visitado em 04 de janeiro de 2013.

5.

↑ Ir para:a b c v-mayakovsky.com. Владимир

Маяковский "Я сам" (em rússo). Visitado em 04 de janeiro de 2013.

6.

Ir para cima↑ ITINERÁRIOS – Revista de Literatura. Suprematismo,

Cubo-futurismo e a Tragédia, de Maiakóvski (PDF). Visitado em 04 de janeiro de 2013.

7.

↑ Ir para:a b Pravda.ru (26 de outubro de 2005). The

death of the poet of communism, Vladimir Mayakovsky, remains mysterious (em inglês) Pravda.ru. Visitado em 22 de fevereiro de 2014.

8.

Ir para cima↑ Boym, Svetlana. Death in Quotation Marks: Cultural Myths of the

Modern Poet (em inglês). [S.l.]: Harvard University Press, 1991. 291 p.

p. 168. ISBN

9780674194274

9.

Ir para cima↑ Wilson, Jason. A Companion to Pablo Neruda: Evaluating Neruda's

Poetry (em inglês). [S.l.]: Tamesis Books, 2008. 255 p. p. 5. ISBN

9781855661677

10.

Ir para cima↑ Arquivo Marxista na Internet (julho de 2005). O

Suicídio de Maiakovsky. Visitado em 04 de janeiro de 2013.

11.

Ir para cima↑ Fernando A. S. Araújo (julho de 2005). O

Suicídio de Maiakovsky Marxists Internet Archive. Visitado em 22 de fevereiro de

2014.

12.

Ir para cima↑ Encyclopedia of World Biography (2004). Vladimir

Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (em inglês). Visitado em 04 de janeiro de 2013.

13.

Ir para cima↑ M. Lawton, Anna; Eagle, Herbert. In: LLC. Words in Revolution:: Russian Futurist Manifestoes, 1912-1928(em inglês). [S.l.]: New Academia Publishing,

2005. 353 p. p. 11. ISBN

0974493473 Página visitada em 04 de janeiro de 2013.

14.

↑ Ir para:a b c Mayakovsky,

Vladimir; Daniels, Guy. Mayakovsky: Plays: European Drama Classics Series (em inglês). [S.l.]: Northwestern University Press,

1968. 274 p. ISBN

0810113392 Página visitada em 04 de janeiro de 2013.

Fonte: Jornal GGN; Miluduarte; Seg, 02/11/2015 -

17:30

Acesso RAS em 27jan2016

O Museu

Mayakovski, um dos mais diferentes e originais de Moscou, situado na praça da

Lubianka, é um dos passeios obrigatórios que o turista que visita a capital

russa deve fazer. Tanto pela importância histórica, quanto literária e cultural

de Vladimir Maiakovski. Como diz a apresentadora do vídeo postado a seguir,

"a excursão pelo Museu Maiakovski é parte de um processo educativo que

nunca acaba". O museu apresenta as cartas, os desenhos, objetos pessoais

do poeta, tudo numa disposição meio anárquica, refletindo o pensamento

tumultuado de Vladimir Maiakovski. Em suma, este museu procura retratar o

mundo, o pensamento e a época do poeta russo, homem sempre atual,de sentimentos

intensos e coração ardente.

Me furto à tentação de colocar sua biografia

neste post, salientando, apenas, que além de poeta, ele era um desenhista de primeira, assim como seus

pais e irmã. Durante os anos da guerra civil, se dedicou a fazer desenhos para

cartazes de propagandas. Fez, também, mais tarde, campanhas institucionais e

propagandas para divulgação da poesia. Muitos de seus desenhos eram de cunho

satírico.

Deixo alguns de exemplo neste espaço.

Agora, ao passeio virtual pelo museu: se você

quiser fazer este passeio em RUSSO, clique AQUI.

Caso não seja da

turminha que conhece ou estuda o idioma do poeta e quiser fazer a visita em

INGLÊS, clique AQUI. Este site, também, oferece um passeio

virtual bastante interativo e nele você vai ouvir a voz do próprio poeta:

Outra opção de

conhecer virtualmente o museu, é este vídeo que se segue:

Finalizo

deixando este link de uma excursão em 3D por todo o museu. Você vai clicando

nas setas ou nas palavras "следующий раздел", localizadas no canto

direito inferior da página, para ir mudando de ambiente. Entre nesta viagem e

se sinta no próprio museu.

E já que o tema

do post é Maiakovski, aí vai um vídeo com raras cenas do poeta. Você poderá

vê-lo por alguns momentos...Cenas do funeral do poeta:

Fontes:

www.youtube.com,

vídeos de debjutlv, Sun Glory e Galina Benislavskaya

http://www.mayakovsky.info/virt/

http://mayakovsky.museum//tour.html

[MAIAKOVSKI COMO DESIGNER GRÁFICO]

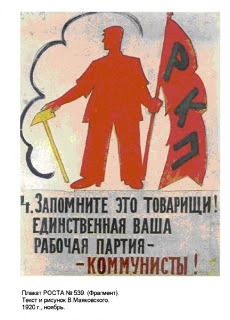

Maiakovski: Lembrem-se

disto, camaradas! é único o vosso partido dos trabalhadores: o dos

comunistas!

|

Maiakovski: desenho de abril

de 1921

|

Maiakovski: Caricatura de

Hugo Gellert, muralista e ilustrador húngaro, contida nas anotações do poeta,

caderno n.33, lista 27, em 1925.Na parte de baixo, dedicatória de Maiakovski

a Gellert, em inglês.

|

Maiakovski: Auto-charge

pouco conhecida, feita para o jornal "chkval", de Odessa, em 1926

|

Texto e desenhos de

Maiakovski, 1920

|

Cartaz feito

por Maiakovski, onde se lê: Rádio, em caixa alta, e, logo

abaixo, o nome do próprio poeta (entre parênteses, ao lado de seu nome,

escrito de forma abreviada 'desenhista". A seguir, os nomes de Vadim

Baian, (ligado ao movimento literário russo do início do século XX), Boris

Popliavski(poeta), entre outros mais desconhecidos desta iletrada blogueira

[Milu Duarte].

|

|

|

|

Maiakovski: desenho de

julho de 1930

|

Maiakovski: "Semana

do movimento Sindical. Fortaleça os sindicatos

|

Saindo dos desenhos, passemos um pouco ao acervo

de fotos do poeta:

|

|

||

Maiakovski em 1900

|

Maiakovski . Ainda

ginasiano, em 1904

|

Maiakovski em 1908

|

|

|

||

Maiakovski em 1910

|

Maiakovski em 1913

|

Maiakovski em 1911, quando

de seu ingresso na Escola de Belas Artes

|

|

|

|

Maiakovski em 1915

|

Maiakovski em 1918

|

|

|

|

Maiakovski em 1927

|

Maiakovski em 1929

|

MAYAKOVSKI - Poemas Traduzidos Selecionados

http://www.poesiaspoemaseversos.com.br/maiakovski/#.Vqkxf_krKM8

BLUSA FÁTUA

Costurarei calças pretas

com o veludo da minha garganta

e uma blusa amarela com três metros de poente.

Pela Niévski do mundo, como criança grande,

andarei, donjuan, com ar de dândi.

com o veludo da minha garganta

e uma blusa amarela com três metros de poente.

Pela Niévski do mundo, como criança grande,

andarei, donjuan, com ar de dândi.

Que a terra gema em sua mole indolência:

“Não viole o verde de as minhas primaveras!”

Mostrando os dentes, rirei ao sol com insolência:

“No asfalto liso hei de rolar as rimas veras!”

“Não viole o verde de as minhas primaveras!”

Mostrando os dentes, rirei ao sol com insolência:

“No asfalto liso hei de rolar as rimas veras!”

Não sei se é porque o céu é azul celeste

e a terra, amante, me estende as mãos ardentes

que eu faço versos alegres como marionetes

e afiados e precisos como palitar dentes!

e a terra, amante, me estende as mãos ardentes

que eu faço versos alegres como marionetes

e afiados e precisos como palitar dentes!

Fêmeas, gamadas em minha carne, e esta

garota que me olha com amor de gêmea,

cubram-me de sorrisos, que eu, poeta,

com flores os bordarei na blusa cor de gema!

garota que me olha com amor de gêmea,

cubram-me de sorrisos, que eu, poeta,

com flores os bordarei na blusa cor de gema!

( Maiakóvski – tradução: Augusto

de Campos )

E ENTÃO, QUE QUEREIS?

Fiz ranger as folhas de jornal

abrindo-lhes as pálpebras piscantes.

E logo

de cada fronteira distante

subiu um cheiro de pólvora

perseguindo-me até em casa.

Nestes últimos vinte anos

nada de novo há

no rugir das tempestades.

abrindo-lhes as pálpebras piscantes.

E logo

de cada fronteira distante

subiu um cheiro de pólvora

perseguindo-me até em casa.

Nestes últimos vinte anos

nada de novo há

no rugir das tempestades.

Não estamos alegres,

é certo,

mas também por que razão

haveríamos de ficar tristes?

O mar da história

é agitado.

As ameaças

e as guerras

havemos de atravessá-las,

rompê-las ao meio,

cortando-as

como uma quilha corta

as ondas.

é certo,

mas também por que razão

haveríamos de ficar tristes?

O mar da história

é agitado.

As ameaças

e as guerras

havemos de atravessá-las,

rompê-las ao meio,

cortando-as

como uma quilha corta

as ondas.

( Maiakóvski,

tradução de E. Carrera Guerra )

*(De outro livro, outro tradutor, outro poema:)

AMO

A Lila Brik

COMUMENTE É ASSIM

Cada um ao nascer

traz sua dose de amor,

mas os empregos,

o dinheiro,

tudo isso,

nos resseca o solo do coração.

Sobre o coração levamos o corpo,

sobre o corpo a camisa,

mas isto é pouco.

Alguém

imbecilmente

inventou os punhos

e sobre os peitos

fez correr o amido de engomar.

Quando velhos se arrependem.

A mulher se pinta.

O homem faz ginástica

pelo sistema Müller.

Mas é tarde.

A pele enche-se de rugas.

O amor floresce,

floresce,

e depois desfolha.

traz sua dose de amor,

mas os empregos,

o dinheiro,

tudo isso,

nos resseca o solo do coração.

Sobre o coração levamos o corpo,

sobre o corpo a camisa,

mas isto é pouco.

Alguém

imbecilmente

inventou os punhos

e sobre os peitos

fez correr o amido de engomar.

Quando velhos se arrependem.

A mulher se pinta.

O homem faz ginástica

pelo sistema Müller.

Mas é tarde.

A pele enche-se de rugas.

O amor floresce,

floresce,

e depois desfolha.

GAROTO

Fui agraciado com o amor sem limites.

Mas, quando garoto,

a gente preocupada trabalhava

e eu escapava

para as margens do rio Rion

e vagava sem fazer nada.

Aborrecia-se minha mãe:

“Garoto danado!”

Meu pai me ameaçava com o cinturão.

Mas eu,

com três rublos falsos,

jogava com os soldados sob os muros.

Sem o peso da camisa,

sem o peso das botas,

de costas ou de barriga no chão,

torrava-me ao sol de Kutaís

até sentir pontadas no coração.

O sol se assombrava:

“Daquele tamaninho

e com um tal coração!

Vai partir-lhe a espinha!

Como, será que cabem

neste tico de gente

o rio,

o coração,

eu

e cem quilômetros de montanhas?”

Mas, quando garoto,

a gente preocupada trabalhava

e eu escapava

para as margens do rio Rion

e vagava sem fazer nada.

Aborrecia-se minha mãe:

“Garoto danado!”

Meu pai me ameaçava com o cinturão.

Mas eu,

com três rublos falsos,

jogava com os soldados sob os muros.

Sem o peso da camisa,

sem o peso das botas,

de costas ou de barriga no chão,

torrava-me ao sol de Kutaís

até sentir pontadas no coração.

O sol se assombrava:

“Daquele tamaninho

e com um tal coração!

Vai partir-lhe a espinha!

Como, será que cabem

neste tico de gente

o rio,

o coração,

eu

e cem quilômetros de montanhas?”

ADOLESCENTE

A juventude tem mil ocupações.

Estudamos gramática até ficar zonzos.

A mim

me expulsaram do quinto ano

e fui entupir os cárceres de Moscou.

Em nosso pequeno mundo caseiro

brotam pelos divãs

poetas de melenas fartas.

Que esperar desses líricos bichanos?

Eu, no entanto,

aprendi a amar no cárcere.

Que vale comparado com isto

a tristeza do bosque de Boulogne?

Que valem comparados com isto

suspiros ante a paisagem do mar?

Eu, pois,

me enamorei da janelinha da cela 103

da “oficina de pompas fúnebres”.

Há gente que vê o sol todos os dias

e se enche de presunção.

“Não valem muito esses raiozinhos”

dizem.

Eu, então,

por um raiozinho de sol amarelo

dançando em minha parede

teria dado todo um mundo.

Estudamos gramática até ficar zonzos.

A mim

me expulsaram do quinto ano

e fui entupir os cárceres de Moscou.

Em nosso pequeno mundo caseiro

brotam pelos divãs

poetas de melenas fartas.

Que esperar desses líricos bichanos?

Eu, no entanto,

aprendi a amar no cárcere.

Que vale comparado com isto

a tristeza do bosque de Boulogne?

Que valem comparados com isto

suspiros ante a paisagem do mar?

Eu, pois,

me enamorei da janelinha da cela 103

da “oficina de pompas fúnebres”.

Há gente que vê o sol todos os dias

e se enche de presunção.

“Não valem muito esses raiozinhos”

dizem.

Eu, então,

por um raiozinho de sol amarelo

dançando em minha parede

teria dado todo um mundo.

MINHA UNIVERSIDADE

Conheceis o francês,

sabeis dividir,

multiplicar,

declinar com perfeição.

Pois, declinai!

Mas sabeis por acaso

cantar em dueto com os edifícios?

Entendeis por acaso

a linguagem dos bondes?

O pintainho humano

mal abandona a casca

atraca-se aos livros

e a resmas de cadernos.

Eu aprendi o alfabeto nos letreiros

folheando páginas de estanho e ferro.

Os professores tomam a terra

e a descarnam

e a descascam

para afinal ensinar:

“Toda ela não passa dum globinho!”

Eu com os costados aprendi geografia.

Não foi à toa que tanto dormi no chão.

Os historiadores levantam

a angustiante questão:

- Era ou não roxa a barba de Barba Roxa?

Que me importa!

Não costumo remexer o pó dessas velharias!

Mas das ruas de Moscou

conheço todas as histórias.

Uma vez instruídos,

há os que propõem

a agradar às damas,

fazendo soar no crânio suas poucas idéias,

como pobres moedas numa caixa de pau.

Eu, somente com os edifícios, conversava.

Somente os canos dágua me respondiam.

Os tetos como orelhas espichando

suas lucarnas atentas

aguardavam as palavras

que eu lhes deitaria.

Depois

noite a dentro

uns com os outros

palravam

girando suas línguas de catavento.

sabeis dividir,

multiplicar,

declinar com perfeição.

Pois, declinai!

Mas sabeis por acaso

cantar em dueto com os edifícios?

Entendeis por acaso

a linguagem dos bondes?

O pintainho humano

mal abandona a casca

atraca-se aos livros

e a resmas de cadernos.

Eu aprendi o alfabeto nos letreiros

folheando páginas de estanho e ferro.

Os professores tomam a terra

e a descarnam

e a descascam

para afinal ensinar:

“Toda ela não passa dum globinho!”

Eu com os costados aprendi geografia.

Não foi à toa que tanto dormi no chão.

Os historiadores levantam

a angustiante questão:

- Era ou não roxa a barba de Barba Roxa?

Que me importa!

Não costumo remexer o pó dessas velharias!

Mas das ruas de Moscou

conheço todas as histórias.

Uma vez instruídos,

há os que propõem

a agradar às damas,

fazendo soar no crânio suas poucas idéias,

como pobres moedas numa caixa de pau.

Eu, somente com os edifícios, conversava.

Somente os canos dágua me respondiam.

Os tetos como orelhas espichando

suas lucarnas atentas

aguardavam as palavras

que eu lhes deitaria.

Depois

noite a dentro

uns com os outros

palravam

girando suas línguas de catavento.

ADULTOS

Os adultos fazem negócios.

Têm rublos nos bolsos.

Quer amor? Pois não!

Ei-lo por cem rublos!

E eu, sem casa e sem teto,

com as mãos metidas nos bolsos rasgados,

vagava assombrado.

À noite

vestis os melhores trajes

e ides descansar sobre viúvas ou casadas.

A mim

Moscou me sufocava de abraços

com seus infinitos anéis de praças.

Nos corações, nos relógios

bate o pêndulo dos amantes.

Como se exaltam as duplas no leito de amor!

Eu, que sou a Praça da Paixão,

surpreendo o pulsar selvagem

do coração das capitais.

Desabotoado, o coração quase de fora,

abria-me ao sol e aos jatos dágua.

Entrai com vossas paixões!

Galgai-me com vossos amores!

Doravante não sou mais dono de meu coração!

Nos demais – eu sei,

qualquer um sabe -

o coração tem domicílio

no peito.

Comigo

a anatomia ficou louca.

Sou todo coração -

em todas as partes palpita.

Oh! quantas são as primaveras

em vinte anos acesas nesta fornalha!

Uma tal carga

acumulada

torna-se simplesmente insuportável.

Insuportável

não para o verso

de veras.

Têm rublos nos bolsos.

Quer amor? Pois não!

Ei-lo por cem rublos!

E eu, sem casa e sem teto,

com as mãos metidas nos bolsos rasgados,

vagava assombrado.

À noite

vestis os melhores trajes

e ides descansar sobre viúvas ou casadas.

A mim

Moscou me sufocava de abraços

com seus infinitos anéis de praças.

Nos corações, nos relógios

bate o pêndulo dos amantes.

Como se exaltam as duplas no leito de amor!

Eu, que sou a Praça da Paixão,

surpreendo o pulsar selvagem

do coração das capitais.

Desabotoado, o coração quase de fora,

abria-me ao sol e aos jatos dágua.

Entrai com vossas paixões!

Galgai-me com vossos amores!

Doravante não sou mais dono de meu coração!

Nos demais – eu sei,

qualquer um sabe -

o coração tem domicílio

no peito.

Comigo

a anatomia ficou louca.

Sou todo coração -

em todas as partes palpita.

Oh! quantas são as primaveras

em vinte anos acesas nesta fornalha!

Uma tal carga

acumulada

torna-se simplesmente insuportável.

Insuportável

não para o verso

de veras.

O QUE ACONTECEU

Mais do que é permitido,

mais do que é preciso,

como um delírio de poeta

sobrecarregando o sonho:

a pelota do coração tornou-se enorme,

enorme o amor,

enorme o ódio.

Sob o fardo,

as pernas vão vacilantes.

Tu o sabes,

sou bem fornido,

entretanto me arrasto,

apêndice do coração,

vergando as espáduas gigantes.

Encho-me dum leite de versos

e, sem poder transbordar,

encho-me mais e mais.

mais do que é preciso,

como um delírio de poeta

sobrecarregando o sonho:

a pelota do coração tornou-se enorme,

enorme o amor,

enorme o ódio.

Sob o fardo,

as pernas vão vacilantes.

Tu o sabes,

sou bem fornido,

entretanto me arrasto,

apêndice do coração,

vergando as espáduas gigantes.

Encho-me dum leite de versos

e, sem poder transbordar,

encho-me mais e mais.

CLAMO

Levantei-o como um atleta,

levei-o como um acrobata,

como se levam os candidatos ao comício,

como nas aldeias se toca a rebate

nos dias de incêndio.

Clamava:

“Aqui está, aqui! Tomai-o!”

Quando este corpanzil se punha a uivar,

as donas

disparando

pelo pó, pelo barro ou pela neve,

como um foguete fugiam de mim.

- “Para nós, algo um tanto menor,

algo assim como um tango…”

Não posso levá-lo

e carrego meu fardo.

Quero arremessá-lo fora

e sei, não o farei.

Os arcos de minhas costelas não resistem.

Sob a pressão

range a caixa torácica.

levei-o como um acrobata,

como se levam os candidatos ao comício,

como nas aldeias se toca a rebate

nos dias de incêndio.

Clamava:

“Aqui está, aqui! Tomai-o!”

Quando este corpanzil se punha a uivar,

as donas

disparando

pelo pó, pelo barro ou pela neve,

como um foguete fugiam de mim.

- “Para nós, algo um tanto menor,

algo assim como um tango…”

Não posso levá-lo

e carrego meu fardo.

Quero arremessá-lo fora

e sei, não o farei.

Os arcos de minhas costelas não resistem.

Sob a pressão

range a caixa torácica.

TU

Entraste.

A sério, olhaste

a estatura,

o bramido

e simplesmente adivinhaste:

uma criança.

Tomaste,

arrancaste-me o coração

e simplesmente foste com ele jogar

como uma menina com sua bola.

E todas,

como se vissem um milagre,

senhoras e senhoritas exclamaram:

- A esse amá-lo?

Se se atira em cima,

derruba a gente!

Ela, com certeza, é domadora!

Por certo, saiu duma jaula!

E eu de júbilo

esqueci o jugo.

Louco de alegria

saltava

como em casamento de índio,

tão leve,

tão bem me sentia.

A sério, olhaste

a estatura,

o bramido

e simplesmente adivinhaste:

uma criança.

Tomaste,

arrancaste-me o coração

e simplesmente foste com ele jogar

como uma menina com sua bola.

E todas,

como se vissem um milagre,

senhoras e senhoritas exclamaram:

- A esse amá-lo?

Se se atira em cima,

derruba a gente!

Ela, com certeza, é domadora!

Por certo, saiu duma jaula!

E eu de júbilo

esqueci o jugo.

Louco de alegria

saltava

como em casamento de índio,

tão leve,

tão bem me sentia.

IMPOSSÍVEL

Sozinho não posso

carregar um piano

e menos ainda um cofre-forte.

Como poderia então

retomar de ti meu coração

e carregá-lo de volta?

Os banqueiros dizem com razão:

“Quando nos faltam bolsos,

nós que somos muitíssimo ricos,

guardamos o dinheiro no banco”.

Em ti

depositei meu amor,

tesouro encerrado em caixa de ferro,

e ando por aí

como um Creso contente.

É natural, pois,

quando me dá vontade,

que eu retire um sorriso,

a metade de um sorriso

ou menos até

e indo com as donas

eu gaste depois da meia-noite

uns quantos rublos de lirismo à toa.

carregar um piano

e menos ainda um cofre-forte.

Como poderia então

retomar de ti meu coração

e carregá-lo de volta?

Os banqueiros dizem com razão:

“Quando nos faltam bolsos,

nós que somos muitíssimo ricos,

guardamos o dinheiro no banco”.

Em ti

depositei meu amor,

tesouro encerrado em caixa de ferro,

e ando por aí

como um Creso contente.

É natural, pois,

quando me dá vontade,

que eu retire um sorriso,

a metade de um sorriso

ou menos até

e indo com as donas

eu gaste depois da meia-noite

uns quantos rublos de lirismo à toa.

O QUE ACONTECEU COMIGO

As esquadras acodem ao porto.

O trem corre para as estações.

Eu, mais depressa ainda,

vou a ti,

atraído, arrebatado,

pois que te amo.

Assim como se apeia

o avarento cavaleiro de Púchkin,

alegre por encafuar-se em seu sótão,

assim eu

regresso ati, amada,

com o coração encantado de mim.

Ficais contentes de retornar à casa.

Ali vos livrais da sujeira,

raspando-vos, lavando-vos,

fazendo a barba.

Assim retorno eu a ti.

Por acaso,

indo a ti não volto à minha casa?

Gente terrena ao seio da terra volta.

Sempre volvemos à nossa meta final.

Assim eu,

em tua direção sempre me inclino

apenas nos separamos

mal acabamos de nos ver.

O trem corre para as estações.

Eu, mais depressa ainda,

vou a ti,

atraído, arrebatado,

pois que te amo.

Assim como se apeia

o avarento cavaleiro de Púchkin,

alegre por encafuar-se em seu sótão,

assim eu

regresso ati, amada,

com o coração encantado de mim.

Ficais contentes de retornar à casa.

Ali vos livrais da sujeira,

raspando-vos, lavando-vos,

fazendo a barba.

Assim retorno eu a ti.

Por acaso,

indo a ti não volto à minha casa?

Gente terrena ao seio da terra volta.

Sempre volvemos à nossa meta final.

Assim eu,

em tua direção sempre me inclino

apenas nos separamos

mal acabamos de nos ver.

DEDUÇÃO

Não acabarão com o amor,

nem as rusgas,

nem a distância.

Está provado,

pensado,

verificado.

Aqui levanto solene

minha estrofe de mil dedos

e faço o juramento:

Amo

firme,

fiel

e verdadeiramente.

nem as rusgas,

nem a distância.

Está provado,

pensado,

verificado.

Aqui levanto solene

minha estrofe de mil dedos

e faço o juramento:

Amo

firme,

fiel

e verdadeiramente.

( Maiakóvski )

(1922 – em Maiacovski – Antologia Poética – tradução E. Carrera Guerra, ed. Max Limonad/SP).

(1922 – em Maiacovski – Antologia Poética – tradução E. Carrera Guerra, ed. Max Limonad/SP).

*

“É melhor morrer de Vodka do que morrer de tédio.”

( Maiakóvski )

*

A EXTRAORDINÁRIA AVENTURA VIVIDA POR VLADÍMIR MAIAKOVSKI NO VERÃO

NA DATCHA

(Púchkino, monte Akula, datcha de Rumiántzev, a 27 verstas

pela estrada de ferro de Iaroslávl)

A tarde ardia com cem sóis.

O verão rolava em julho.

O calor se enrolava

no ar e nos lençóis

da datcha onde eu estava.

Na colina de Púchkino, corcunda,

o monte Akula,

e ao pé do monte

a aldeia enruga

a casa dos telhados.

E atrás da aldeia,

um buraco

e no buraco, todo dia,

o mesmo ato:

o sol descia

lento e exato.

E de manhã

outra vez

por toda a parte

lá estava o sol

escarlate.

Dia após dia

isto

começou a irritar-me

terrivelmente.

Um dia me enfureço a tal ponto

que, de pavor, tudo empalidece.

E grito ao sol, de pronto:

“Desce!

Chega de vadiar nessa fornalha!”

E grito ao sol:

“Parasita!

Você, aí, a flanar pelos ares,

e eu, aqui, cheio de tinta,

com a cara nos cartazes!”

E grito ao sol:

“Espere!

Ouça, topete de ouro,

e se em lugar

desse ocaso

de paxá

você baixar em casa

para um chá?”

Que mosca me mordeu!

É o meu fim!

Para mim

sem perder tempo

o sol

alargando os raios-passos

avança pelo campo.

Não quero mostrar medo.

Recuo para o quarto.

Seus olhos brilham no jardim.

Avançam mais.

Pelas janelas,

pelas portas,

pelas frestas,

a massa

solar vem abaixo

e invade a minha casa.

Recobrando o fôlego,

me diz o sol com voz de baixo:

“Pela primeira vez recolho o fogo,

desde que o mundo foi criado.

Você me chamou?

Apanhe o chá,

pegue a compota, poeta!”

Lágrimas na ponta dos olhos

- o calor me fazia desvairar -

eu lhe mostro

o samovar:

O verão rolava em julho.

O calor se enrolava

no ar e nos lençóis

da datcha onde eu estava.

Na colina de Púchkino, corcunda,

o monte Akula,

e ao pé do monte

a aldeia enruga

a casa dos telhados.

E atrás da aldeia,

um buraco

e no buraco, todo dia,

o mesmo ato:

o sol descia

lento e exato.

E de manhã

outra vez

por toda a parte

lá estava o sol

escarlate.

Dia após dia

isto

começou a irritar-me

terrivelmente.

Um dia me enfureço a tal ponto

que, de pavor, tudo empalidece.

E grito ao sol, de pronto:

“Desce!

Chega de vadiar nessa fornalha!”

E grito ao sol:

“Parasita!

Você, aí, a flanar pelos ares,

e eu, aqui, cheio de tinta,

com a cara nos cartazes!”

E grito ao sol:

“Espere!

Ouça, topete de ouro,

e se em lugar

desse ocaso

de paxá

você baixar em casa

para um chá?”

Que mosca me mordeu!

É o meu fim!

Para mim

sem perder tempo

o sol

alargando os raios-passos

avança pelo campo.

Não quero mostrar medo.

Recuo para o quarto.

Seus olhos brilham no jardim.

Avançam mais.

Pelas janelas,

pelas portas,

pelas frestas,

a massa

solar vem abaixo

e invade a minha casa.

Recobrando o fôlego,

me diz o sol com voz de baixo:

“Pela primeira vez recolho o fogo,

desde que o mundo foi criado.

Você me chamou?

Apanhe o chá,

pegue a compota, poeta!”

Lágrimas na ponta dos olhos

- o calor me fazia desvairar -

eu lhe mostro

o samovar:

“Pois bem,

sente-se, astro!”

Quem me mandou berrar ao sol

insolências sem conta?

Contrafeito

me sento numa ponta

do banco e espero a conta

com um frio no peito.

Mas uma estranha claridade

fluía sobre o quarto

e esquecendo os cuidados

começo

pouco a pouco

a palestrar com o astro.

Falo

disso e daquilo,

como me cansa a Rosta,

etc.

E o sol:

“Está certo,

mas não se desgoste,

não pinte as coisas tão pretas.

E eu? Você pensa

que brilhar

é fácil?

Prove, pra ver!

Mas quando se começa

é preciso prosseguir

e a gente vai e brilha pra valer!”

Conversamos até a noite

ou até o que, antes, eram trevas.

Como falar, ali, de sombras?

Ficamos íntimos,

os dois.

Logo,

com desassombro,

estou batendo no seu ombro.

E o sol, por fim:

“Somos amigos

pra sempre, eu de você,

você de mim.

Vamos poeta,

cantar,

luzir

no lixo cinza do universo.

Eu verterei o meu sol

e você o seu

com seus versos.”

O muro das sombras,

prisão das trevas,

desaba sob o obus

dos nossos sóis de duas bocas.

Confusão de poesia e luz,

chamas por toda a parte.

Se o sol se cansa

e a noite lenta

quer ir pra cama,

marmota sonolenta,

eu, de repente,

inflamo a minha flama

e o dia fulge novamente.

Brilhar pra sempre,

brilhar como um farol,

brilhar com brilho eterno,

gente é pra brilhar,

que tudo mais vá pro inferno,

este é o meu slogan

e o do sol.

1920

( Maiakóvski ) (tradução de Augusto de Campos)

(1. Datcha – casa de veraneio.

2. Versta – medida itinerária equivalente a 1,067m.

3. Rosta – A Agência Telegráfica Russa, para a qual Maiakovski executou cartazes satíricos de notícias – as “janelas” Rosta -, de 1919 a 1922.)

2. Versta – medida itinerária equivalente a 1,067m.

3. Rosta – A Agência Telegráfica Russa, para a qual Maiakovski executou cartazes satíricos de notícias – as “janelas” Rosta -, de 1919 a 1922.)

*

A

PLENOS PULMÕES

Primeira Introdução ao Poema

Caros

camaradas

futuros!

Revolvendo

a merda fóssil

de agora,

pesquisando

estes dias escuros,

talvez

perguntareis

por mim.

camaradas

futuros!

Revolvendo

a merda fóssil

de agora,

pesquisando

estes dias escuros,

talvez

perguntareis

por mim.

Ora,

começará

vosso homem de ciência,

afagando os porquês

num banho de sabença,

conta-se

que outrora

um férvido cantor

a água sem fervura

combateu com fervor(1).

Professor,

jogue fora

suas lentes de arame!

A mim cabe falar

de mim

de minha era.

Eu ? incinerador,

eu ? sanitarista,

a revolução

me convoca e me alista.

começará

vosso homem de ciência,

afagando os porquês

num banho de sabença,

conta-se

que outrora

um férvido cantor

a água sem fervura

combateu com fervor(1).

Professor,

jogue fora

suas lentes de arame!

A mim cabe falar

de mim

de minha era.

Eu ? incinerador,

eu ? sanitarista,

a revolução

me convoca e me alista.

Troco pelo front

a horticultura airosa

da poesia ?

fêmea caprichosa.

Ela ajardina o jardim virgem

vargem

sombra

alfombra.

“É assim o jardim de jasmim,

o jardim de jasmim do alfenim.”

Este verte versos feito regador,

aquele os baba,

boca em babador, ?

bonifrates encapelados,

descabelados vates ?

entendê-los,

ao diabo!,

quem há-de…

Quarentena é inútil contra eles

? mandolinam por detrás das paredes:

“Ta-ran-tin, ta-ran-tin,

ta-ran-ten-n-n…”

Triste honra,

se de tais rosas

minha estátua se erigisse:

na praça

escarra a tuberculose;

putas e rufiões

numa ronda de sífilis.

Também a mim

a propaganda

cansa,

é tão fácil

alinhavar

romanças, ?

Mas eu

me dominava

entretanto

e pisava

a garganta do meu canto.

Escutai,

camaradas futuros,

o agitador,

o cáustico caudilho,

o extintor

dos melífluos enxurros:

por cima

dos opúsculos líricos,

eu vos falo

como um vivo aos vivos.

Chego a vós,

à Comuna distante,

não como Iessiênin,

guitarriarcaico.

Mas através

dos séculos em arco

sobre os poetas

e sobre os governantes.

Meu verso chegará,

não como a seta

lírico-amável,

que persegue a caça.

Nem como

ao numismata

a moeda gasta,

nem como a luz

das estrelas decrépitas.

Meu verso

com suor

rompe a mole dos anos,

e assoma

a olho nu,

palpável,

bruto,

como a nossos dias

chega o aqueduto

levantado

por escravos romanos.

No túmulo dos livros,

versos como ossos,

se estas estrofes de aço

acaso descobrirdes,

vós as respeitareis,

como quem vê destroços

de um arsenal antigo,

mas terrível.

Ao ouvido

não diz

blandícias

minha voz;

lóbulos de donzelas

de cachos e bandós

não faço enrubescer

com lascivos rondós.

Desdobro minhas páginas?

versos como ossos,

se estas estrofes de aço

acaso descobrirdes,

vós as respeitareis,

como quem vê destroços

de um arsenal antigo,

mas terrível.

Ao ouvido

não diz

blandícias

minha voz;

lóbulos de donzelas

de cachos e bandós

não faço enrubescer

com lascivos rondós.

Desdobro minhas páginas?

tropas em parada,

e passo em revista

o front das palavras.

Estrofes estacam

chumbo-severas,

prontas para o triunfo

ou para a morte.

Poemas-canhões, rígida coorte,

apontando

as maiúsculas

abertas.

Ei-la,

a cavalaria do sarcasmo,

minha arma favorita,

alerta para a luta.

Rimas em riste,

sofreando o entusiasmo,

eriça

suas lanças agudas.

E todo

este exército aguerrido,

vinte anos de combates,

não batido,

eu vos dôo,

proletários do planeta,

cada folha

até a última letra.

O inimigo

da colossal

classe obreira,

é também

meu inimigo

mortal.

e passo em revista

o front das palavras.

Estrofes estacam

chumbo-severas,

prontas para o triunfo

ou para a morte.

Poemas-canhões, rígida coorte,

apontando

as maiúsculas

abertas.

Ei-la,

a cavalaria do sarcasmo,

minha arma favorita,

alerta para a luta.

Rimas em riste,

sofreando o entusiasmo,

eriça

suas lanças agudas.

E todo

este exército aguerrido,

vinte anos de combates,

não batido,

eu vos dôo,

proletários do planeta,

cada folha

até a última letra.

O inimigo

da colossal

classe obreira,

é também

meu inimigo

mortal.

Anos de servidão e de miséria

comandavam

nossa bandeira vermelha.

Nós abríamos Marx

volume após volume,

janelas

de nossa casa

abertas amplamente,

mas ainda sem ler

saberíamos o rumo!

onde combater,

de que lado,

em que frente.

Dialética,

não aprendemos com Hegel.

Invadiu-nos os versos

ao fragor das batalhas,

quando,

sob o nosso projétil,

debandava o burguês

que antes nos debandara.

Que essa viúva desolada,

? glória ?

se arraste

após os gênios,

melancólica.

Morre,

meu verso,

como um soldado

anônimo

na lufada do assalto.

Cuspo

sobre o bronze pesadíssimo,

sobre o bronze pesadíssimo,

cuspo

sobre o mármore viscoso.

Partilhemos a glória, ?

entre nós todos, ?

o comum monumento:

o socialismo,

forjado

na refrega

e no fogo.

Vindouros,

varejai vossos léxicos:

do Letes

brotam letras como lixo ?

“tuberculose”,

“bloqueio”,

“meretrício”.

Por vós,

geração de saudáveis, ?

um poeta,

com a língua dos cartazes,

lambeu

os escarros da tísis.

A cauda dos anos

faz-me agora

um monstro,

antediluviano.

Camarada vida,

vamos,

para diante,

galopemos

pelo qüinqüênio afora(2).

sobre o mármore viscoso.

Partilhemos a glória, ?

entre nós todos, ?

o comum monumento:

o socialismo,

forjado

na refrega

e no fogo.

Vindouros,

varejai vossos léxicos:

do Letes

brotam letras como lixo ?

“tuberculose”,

“bloqueio”,

“meretrício”.

Por vós,

geração de saudáveis, ?

um poeta,

com a língua dos cartazes,

lambeu

os escarros da tísis.

A cauda dos anos

faz-me agora

um monstro,

antediluviano.

Camarada vida,

vamos,

para diante,

galopemos

pelo qüinqüênio afora(2).

Os versos

para mim

não deram rublos,

nem mobílias

de madeiras caras.

Uma camisa

lavada e clara,

e basta, ?

para mim é tudo.

Ao Comitê Central

do futuro

ofuscante,

sobre a malta

dos vates

velhacos e falsários,

apresento

em lugar

do registro partidário

todos

os cem tomos

dos meus livros militantes.

dezembro 1929/janeiro

1930

1. Maiakóvski escreveu versos de propaganda

sanitária.

2. Alusão aos Planos Qüinqüenais soviéticos.

(Tradução e notas de Haroldo

de Campos)

Do livro “Maiakovski – Poemas”/Editora Perspectiva,

1982.

Leia também:

Vladimir Mayakovsky

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Mayakovsky"

redirects here. For other uses, see Mayakovsky

(disambiguation).

Acesso RAS em 27jan2016

Vladimir Mayakovsky

|

|

|

Mayakovsky in 1924

|

|

Born

|

|

Died

|

|

Citizenship

|

|

Alma mater

|

|

Period

|

1912—1930

|

Literary movement

|

|

Vladimir Vladimirovich

Mayakovsky (/ˌmɑːjəˈkɔːfski, -ˈkɒf-/;[1] Russian: Влади́мир Влади́мирович Маяко́вский; July 19 [O.S. July

7] 1893 – 14 April 1930) was aRussian Soviet poet, playwright, artist and stage and film actor.

During his early, pre-Revolution period leading into 1917, Mayakovsky

became renowned as a prominent figure of the Russian Futurist movement; being among the signers of

the Futurist manifesto, A Slap

in the Face of Public Taste (1913),

and authoring poems such as A Cloud in Trousers (1915) and Backbone Flute (1916). Mayakovsky produced a large

and diverse body of work during the course of his career: he wrote poems, wrote

and directed plays, appeared in films, edited the art journal LEF, and created agitprop posters

in support of the Communist

Party during the Russian Civil War. Though Mayakovsky's work

regularly demonstrated ideological and patriotic support for the ideology of

the Communist

Party and a strong

admiration of Lenin,[2][3] Mayakovsky's

relationship with the Soviet state was always complex and often tumultuous.

Mayakovsky often found himself engaged in confrontation with the increasing

involvement of the Soviet State in cultural

censorship and the

development of the State doctrine of Socialist realism. Works that contained

criticism or satire of aspects of the Soviet system, such as the poem

"Talking With the Taxman About Poetry" (1926), and the plays The Bedbug (1929) and The Bathhouse (1929), were met with scorn by the

Soviet state and literary establishment.

In 1930 Mayakovsky committed suicide. Even after death

his relationship with the Soviet state remained unsteady. Though Mayakovsky had

previously been harshly criticized by Stalinist governmental bodies like RAPP, Joseph Stalin posthumously declared Mayakovsky "the

best and the most talented poet of our Soviet epoch."[4]

BIOGRAPHY

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky was born the last of

three children in Baghdati, Kutaisi Governorate, Georgia, then part of the Russian Empire. His father Vladimir

Konstantinovich Mayakovsky, a local forester, belonged to a noble family and

was a distant relative of the writer Grigory Danilevsky.

Vladimir Vladimirovich's mother Alexandra Alexeyevna (née Pavlenko), was a

housewife, looking after the children – a son and two daughters, Olga and

Lyudmila (their brother Konstantin died at the age of three).[5]

The Mayakovskys in Kutaisi

The family had Russian and Zaporozhian Cossack

descent on their father's side and Ukrainian on their mother's.[6] At

home the family spoke Russian. With his friends and at school Mayakovky used Georgian. "I was born in the Caucasus, my

father is a Cossack, my mother is Ukrainian. My mother tongue is Georgian. Thus

three cultures are united in me", he told the Prague newspaper Prager Presse in a 1927 interview.[7] Georgia

for Mayakovsky remained the eternal symbol of beauty. "I know, it's

nonsense, Eden and Paradise, but since people sang about them // It must have

been Georgia, the joyful land, that those poets were having in mind", he

wrote later.[5][8]

In 1902 Mayakovsky joined the Kutais gymnasium where, as a 14-year-old he took part

in socialist demonstrations

at the town of Kutaisi.[5] His

mother, aware of his activities, apparently didn't mind. "People around

warned us we were giving a young boy too much freedom. But I saw him developing

according to the new trends, sympathized with him and pandered to his

aspirations", she later remembered.[6] After

the sudden and premature death of his father in 1906 (he pricked his finger

with a rusty pin while filing papers and died of blood poisoning) the family — Mayakovsky, his

mother, and his two sisters — moved to Moscow after

selling all their movable property.[5][9]

In July 1906 Mayakovsky joined the 4th form of the

Moscow's 5th Classic gymnasium and soon developed a passion for Marxist literature.

"Never cared for fiction. For me it was philosophy, Hegel,

natural sciences, but first and foremost, Marxism. There'd be no higher art for

me than "The Foreword" by Marx, he recalled in the 1920s in his

autobiographyI, Myself.[10] In

1907 Mayakovsky became a member of his gymnasium's underground Social

Democrats' circle, taking part in numerous activities of the Russian

Social Democratic Labour Party which

he, given the nickname "Comrade Konstantin",[11] joined

the same year.[12][13] In

1908, the boy was dismissed from the gymnasium because his mother was no longer

able to afford the tuition fees.[14] For

two years he studied at the Stroganov School of Industrial Arts, where his

sister Lyudmila had started her studies a few years earlier.[9]

Mayakovsky in 1910

As a young Bolshevik activist,

Mayakovsky distributed propaganda leaflets, possessed a pistol without a

license, and in 1909 got involved in smuggling female political prisoners out

of prison. This resulted in a series of arrests and finally an 11-month

imprisonment.[11] It

was in a solitary confinement of the Moscow Butyrka prison that Mayakovsky started writing verses

for the first time.[15] "Revolution

and poetry got entangled in my head and became one", he wrote in the I, Myself autobiography.[5] As

an underage person, Mayakovsky avoided a serious prison sentence (with

subsequent deportation) and in January 1910 was released.[14] A

warden confiscated the young man's notebook, and years later Mayakovsky

conceded that was all for the better, yet he always cited 1909 as the year his

literary career started.[5]

Upon his release from prison, Mayakovsky remained an

ardent Socialist, but realized his own inadequacy as a serious revolutionary.

Having left the Party (never to re-join it), he concentrated on education.

"I stopped my Party activities. Sat down and started to learn… Now my

intention was to make the Socialist art", he later remembered.[16]

In 1911 Mayakovsky enrolled in the Moscow Art School. In September 1911 a brief

encounter with fellow student David Burlyuk (which nearly ended with a fight) led

to lasting friendship and had historic consequences for the nascent Russian

Futurist movement.[12][15] Mayakovsky

became an active member (and soon a spokesman) for the group Gileas (Гилея), which sought to free the arts

from academic traditions: its members would read poetry on street corners,

throw tea at their audiences, and make their public appearances an annoyance

for the art establishment.[9]

Burlyuk, on having heard Mayakovsky's verses, declared

him "a genius poet".[14][17] Later

Soviet researchers tried to downplay the significance of the fact, but even

after their friendship ended and their ways parted, Mayakovsky continued to

give credit to his mentor, referring to him as "my wonderful friend".

"It was Burlyuk who turned me into a poet. He read the French and the

Germans to me. He pressed books on me. He would come and talk endlessly. He

didn't let me get away. He would subside me with 50 kopeks each day so as I’d

write and not be hungry", Mayakovsky wrote in "I, Myself".[11]

LITERARY CAREER

Mayakovsky (center) with the fellow Futurist group members

On 17 November 1912, Mayakovsky made his first public

performance on stage of the Stray Dog artistic basement in Saint Petersburg.[12] In

December of that year his first published poems, "Night" (Ночь) and

"Morning" (Утро) appeared in the Futurists' Manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste,[18] signed

by Mayakovsky, as well as Velemir Khlebnikov,

David Burlyuk and Alexey Kruchenykh, calling among other things

for… "throwing Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, etc, etc, off the steamboat of the

modernity."[12][14]

In October 1913 Mayakovsky gave the performance at the

Pink Lantern café, reciting his new poem "Take That!" (Нате!) for the

first time. The concert at the Petersburg's Luna-Park saw the premiere of the

poetic monodrama Vladimir

Mayakovsky, with the author in a leading role, stage decorations

designed by Pavel Filonov and Iosif Shkolnik.[12][15] In

1913 Mayakovsky's first poetry collection called I (Я) came out, its original limited

edition 300 copies lithographically printed. This four-poem cycle,

handwritten and illustrated by Vasily Tchekrygin and Leo Shektel, later formed

Part One of the 1916 compilation Simple

as Mooing.[14]

In December 1913 year Mayakovsky along with his fellow

Futurist group members embarked on the Russian tour, which took them to 17

cities, including Simferopol, Sevastopol,Kerch, Odessa and Kishinev.[5] It

was a riotous affair. The audiences would go wild and often the police stopped

the readings. The poets dressed outlandishly, and Mayakovsky, "a regular

scandal-maker" in his own words, used to appear on stage in a self-made

yellow shirt which became the token of his early stage persona.[11] The

tour ended on 13 April 1914 in Kaluga[12] and

cost Mayakovsky and Burlyuk their education: both were expelled from the Art

school for their public appearances deemed incompatible with the school's

academic principles.[12][14] They

learned of it while in Poltava from

the local police chief, who chose the occasion as a pretext to ban the

Futurists from performing on stage.[6]

Having won 65 rubles in lottery, in May 1914 Mayakovsky

went to Kuokkala, near Petrograd. Here he put the

finishing touches to A Cloud in Trousers,

frequented Korney Chukovsky's dacha,

sat for Ilya Repin's painting sessions and met Maxim Gorky for

the first time.[19] As World War I began,

Mayakovsky volunteered but was rejected as "politically unreliable".

He worked for a time at the Lubok Today company which produced patriotic lubok pictures, and in the Nov (Virgin Land) newspaper, which

published several of his anti-war poems ("Mother and an Evening Killed by

the Germans", "The War is Declared", "Me and Napoleon"

among others).[6] In

summer 1915 Mayakovsky moved to Petrograd where he started contributing to the New Satyrikon magazine, writing mostly humorous verse

in the vein of Sasha Tchorny, one of the journal's former

stalwarts. Then Maxim Gorky invited the poet to work for his journal, Letopis[5][16] (Chronicle).

In June of that year Mayakovsky fell in love with a

married woman, Lilya Brik, who eagerly took upon herself the

role of a "muse". Her husband Osip Brik seemed

not to mind and became the poet's close friend; later he published several

books by Mayakovsky and used his entrepreneurial talents to support the

Futurist movement. This love affair, as well as his impressions of World War I

and Socialism, strongly influenced Mayakovsky's best known works: A Cloud in Trousers (1915),[20] his

first major poem of appreciable length, followed by Backbone Flute (1915), The War and the World (1916) and The Man (1918).[12]

When his mobilization form finally arrived in the autumn

of 1915, Mayakovsky found himself unwilling to go to the frontlines. Assisted

by Gorky, he joined the Petrograd Military Driving school as a draftsman and

was studying there until early 1917.[7][12] In

1916 Parus (The Sail) Publishers (again led by Gorky), published Mayakovsky's

poetry compilation called Simple

As Mooing.[5][12]

1917–1927

Photo c. 1914 (caption: "Futurist

Vladimir Mayakovsky")

Mayakovsky embraced the Bolshevik

Russian Revolution wholeheartedly

and for a while even worked in Smolny, Petrograd, where he saw Vladimir Lenin and was rubbing shoulders with the

revolutionary soldiers.[12] "To

accept or not to accept, there was no such question… [That was] my Revolution,"

he wrote in I, Myself autobiography.[7] In

November 1917 he took part in the Communist Party's Central

committee-sanctioned assembly of writers, painters and theater directors who

expressed their allegiance to the new political regime.[12] In

December that year "The Left March" (Левый мар,1918) was premiered at

the The Navy Theater, with sailors as an audience.[16]

In 1918 Mayakovsky started the short-lived Futurist Paper. He also starred

in three silent films made

at the Neptun Studios in Petrograd he had written scripts for. The only

surviving one, The Young Lady

and the Hooligan, was based on the La

maestrina degli operai (The

Workers' Young Schoolmistress) published in 1895 by Edmondo De Amicis, and directed by Evgeny

Slavinsky. The other two, Born

Not for the Money and Shackled by Film were directed by Nikandr Turkin and

are presumed lost.[12][21]

On 7 November 1918 Mayakovsky's play Mystery-Bouffe was premiered in the Petrograd Musical

Drama Theatre.[12] Representing

a universal flood and the subsequent joyful triumph of the "Unclean"

(the proletariat) over the "Clean" (the bourgeoisie), this satirical

drama was re-worked in 1921 to even greater popular acclaim.[15][16] However,

the author's attempt to make a film of the play failed, the Moscow Soviet

finding its language "incomprehensible for the masses."[9]

In March 1919 Mayakovsky moved back to Moscow where Vladimir Mayakovsky's Collected Works

1909–1919 was released. The

same month he started working for the Russian State Telegraph Agency (ROSTA)

creating — both graphic and text — satirical Agitprop posters,

aimed mostly at informing the country’s largely illiterate population of the

current events.[7][12] In

the cultural climate of the early Soviet Union, his popularity grew rapidly,

even if among the members of the first Bolshevik government, only Anatoly Lunacharsky supported him; others treated the

Futurist art more skeptically. Mayakovsky's 1921 poem, 150 000 000 failed to impress Lenin, who

apparently saw in it little more than a formal futuristic experiment. More

favourably received by the Soviet leader was his next one, "Re

Conferences" which came out in April.[12]

A vigorous spokesman for the Communist Party, Mayakovsky

expressed himself in many ways. Contributing simultaneously to numerous Soviet

newspapers, he poured out topical propagandistic verses and wrote didactic booklets

for children while lecturing and reciting all over Russia.[15]

In May 1922, after a performance at the House of

Publishing at the charity auction collecting money for the victims of Povolzhye famine,

he went abroad for the first time, visiting Riga, Berlin and Paris where he visited the studios of Léger and Picasso.[9] Several

books, including The West and Paris cycles (1922–1925) came out as a

result.[12]

Mayakovsky (third from right) with friends

including Lilya Brik, Eisenstein (third

from left) and Boris Pasternak (second from left).

From 1922 to 1928, Mayakovsky was a prominent member of

the Left Art Front (LEF) he helped to found (and coin its "literature of

fact, not fiction" credo) and for a while defined his work as Communist

Futurism (комфут).[14] He

edited, along with Sergei Tretyakov and Osip Brik, the journal LEF, its stated objective being

"re-examining the ideology and practices of the so-called leftist art,

rejecting individualism and increasing Art's value for the developing

Communism."[13] The

journal's first, March 1923, issue featured Mayakovsky's poem About That (Про это).[12] Regarded

as a LEF manifesto, it soon came out as a book

illustrated by Alexander Rodchenko who also used some photographs made by

Mayakovsky and Lilya Brik.[22]

In May 1923 Mayakovsky spoke at a massive protest rally

in Moscow, in the wake of Vatslav Vorovsky's assassination. In October

1924 he gave numerous public readings of the 3,000-line epic Vladimir

Ilyich Lenin written

on the death of the Soviet Communist leader. Next February it came out as a

book, published by Gosizdat. Five years later Mayakovsky's rendition of the

third part of the poem, at the Lenin Memorial evening in the Bolshoi Theatre ended with 20-minutes ovation.[15][23] In

May 1925 Mayakovsky's second trip took him to several European cities, then to

the United States, Mexico and Cuba.

The book of essays My Discovery

of America came out later

that year.[12][14]

In January 1927 the first issue of the New LEF magazine came out, again under

Mayakovsky's supervision, now focusing on the documentary art. In all, 24

issues of it came out.[17] In

October 1927 Mayakovsky recited his new poem All

Right! (Хорошо!) for the

audience of the Moscow Party conference activists in the Moscow's Red Hall.[12] In

November 1927 a theatre puction called The

25th (and based upon the All Right! poem) was premiered in the Leningrad

Maly Opera Theatre. In summer 1928, disillusioned with LEF, he left both the

organization and its magazine.[12]

1929–1930

Mayakovsky

at his 20 Years of Work exhibition, 1930

In 1929 the publishing house Goslitizdat released The Works by V.V. Mayakovsky in 4 volumes. In September 1929 the

first assembly of the newly formed REF group gathered with Mayakovsky in the

chair.[12] But

behind this façade the poet's relationship with the Soviet literary

establishment was quickly deteriorating. Both the REF-organized exhibition of

Mayakovsky's work, celebrating the 20th anniversary of his literary career and

the parallel event in the Writers' Club, "20 Years of Work" in

February 1930, were ignored by the RAPP members and, more importantly, the

Party leadership, particularly Stalin whose

attendance he was greatly anticipating. It was becoming evident that the

experimental art was no longer welcomed by the regime, and the country's most

famous poet irritated a lot of people.[6]

Two of Mayakovsky's satirical plays, written specifically

for Meyerkhold Theatre, The Bedbug (1929) and (in particular) The Bathhouse (1930) evoked stormy criticism from

the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers.[13] In

February 1930 Mayakovsky joined RAPP, only to find himself labeled poputchik which

from the days of Lenin amounted to a potentially deadly political accusation.[12] The

smear campaign was started in the Soviet press, sporting slogans like

"Down with Mayakovshchina!" On 9 April 1930 Mayakovsky, reading his

new poem "At the Top of My Voice", was shouted down by the student

audience, for being "too obscure."[5][24]

DEATH

On 12 April 1930, Mayakovsky was for the last time seen

in public: he took part in the discussion at the Sovnarkom meeting concerning the proposed

copyright law.[12]. On

14 April 1930, his current partner, actress Veronika Polonskaya, upon leaving

his flat, heard a shot behind the closed door. She rushed in and found the poet

lying on the floor; he apparently shot himself through the heart.[12][25] The

handwritten death note read: "To all of you. I die, but don't blame anyone

for it, and please do not gossip. The deceased terribly disliked this sort of

thing. Mother, sisters, comrades, forgive me—this is not a good method (I do

not recommend it to others), but there is no other way out for me. Lily – love

me. Comrade Government, my family consists of Lily Brik, mama, my sisters, and

Veronika Vitoldovna Polonskaya. If you can provide a decent life for them,

thank you. Give the poem I started to the Briks. They’ll understand."[7] The

"unfinished poem" in his suicide note read, in part: "And so

they say – "the incident dissolved" / the love boat smashed up / on

the dreary routine. / I'm through with life / and [we] should absolve /from

mutual hurts, afflictions and spleen."[26] Mayakovsky's

funeral on 17 April 1930, was attended by around 150,000, the third largest

event of public mourning in Soviet history, surpassed only by those of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin.[4][27] He

was interred at the Moscow Novodevichy Cemetery.[13]

CONTROVERSY SURROUNDING DEATH

Mayakovsky's farewell letter

On the day of Mayakovsky's death, 14 April, ROSTA published a news bulletin, reprinted

in Pravda the

following day, that read in part: "the suicide was caused by reasons of a

purely personal order, having nothing in general to do with the public and

literary activity of the poet, the suicide was preceded by an illness from

which the poet still had not completely recovered."[citation needed] Mayakovsky's suicide occurred after a

dispute with Polonskaya, with whom he had a brief but unstable romance.

Polonskaya, who was in love with the poet, but unwilling to leave her husband,

was the last one to see Mayakovsky alive.[7] But,

as Lilya Brik stated in her memoirs, "the idea of suicide was like a

chronic disease inside him, and like any chronic disease it worsened under

circumstances that, for him, were undesirable ... "[11] According

to Polonskaya, Mayakovsky mentioned suicide on 13 April, when the two were at Valentin Katayev's place, but she thought he

was trying to emotionally blackmail her and "refused to believe for a

second [he] could do such a thing."[25]

Yet speculation has occurred regarding the circumstances

of Mayakovsky's death. It appeared that the suicide note was written two days

before his death. Soon after the poet's death, Lilya and Osip Briks were

hastily sent abroad. The bullet removed from his body didn't match the model of

his pistol, and his neighbors were later reported to say they'd heard two

shots.[11] Ten

days later, the officer investigating the poet's suicide was himself killed,

fueling speculation about the nature of Mayakovsky's death.[13]Such speculation, often alluding to

suspicion of murder by State services, especially intensified during the

periods of Krushchevian de-Stalinisation, Glasnost, and Perestroika,[dubious ] as Soviet politicians sought to weaken

Stalin's reputation (or Brik's, and by association, Stalin's) and the positions

of contemporary opponents. According to Chantal Sundaram:

The extent to which rumours of Mayakovsky's murder

remained widespread is indicated by the fact that even as late as the end of

1991 they prompted the State Mayakovsky Museum to commission an expert medical

and criminological inquiry into the material evidence of his death kept in the

museum: photographs, the shirt with traces from the gunshot, the carpet on

which Mayakovsky fell, and the authenticity of the suicide note. The

possibility of a forgery, suggested by [Andrei] Koloskov, had survived as a

theory with different variants. But the results of a detailed hand-writing

analysis found that the suicide note was undoubtedly written by Mayakovsky, and

also included the conclusion that its irregularities "depict a diagnostic

complex, testifying to the influence ... at the moment of execution ... of

'disconcerting' factors, among which the most probable is a

psycho-physiological state linked with agitation." Although the findings

are hardly surprising, the event is indicative of a fascination with

Mayakovsky's contradictory relationship with the Soviet authorities which

survived into the era of perestroika, despite the fact that he was being

attacked and rejected for his political conformism at this time.[4]

PRIVATE LIFE

Mayakovsky met husband and wife Osip and Lilya Briks in

July 1915 at their dacha in Malakhovka nearby

Moscow. Soon after that Lilya's sister Elsa, who'd had a brief affair with the poet

before, invited him to the Briks' Petrograd flat. The couple at the time showed

no interest in literature and were successful corals traders.[28] That

evening Mayakovsky recited the yet unpublished poem A Cloud in Trousers and announced it as dedicated to the

hostess ("For you, Lilya"). "That was the happiest day in my

life," was how he referred to the episode in his autobiography years

later.[5] According

to Lilya Brik's memoirs, her husband too fell in love with the poet ("How

could I have possibly failed to fell for him, if Osya loved him so?" – she

once argued),[29] whereas

"Volodya did not merely fall in love with me; he attacked me, it was an

assault. For two and a half years I didn't have a moment's peace. I understood

right away that Volodya was a genius, but I didn't like him. I didn't like

clamorous people ... I didn't like the fact that he was so tall and people in

the street would stare at him; I was annoyed that he enjoyed listening to his

own voice, I couldn't even stand the name Mayakovsky... sounding so much like a

cheap pen name."[11] Both

Mayakovsky's persistent adoration and rough appearance irritated her. It was,

allegedly, to please her, that Mayakovsky attended a dentist, started to wear a

bow tie and use a walking stick.[9]

Soon after Osip Brik published A Cloud in Trousers in September 1915, Mayakovsky settled

in the Palace Royal hotel at the Pushkinskaya Street, Petrograd, not far from

where they lived. He introduced the couple to his Futurist friends and the

Briks' flat quickly evolved into a modern literary salon. From then on

Mayakovsky was dedicating every one of his large poems (with the obvious

exception of Vladimir Ilyich

Lenin) to Lilya; such dedications later started to appear even in the texts

he'd written before they met, much to her displeasure.[11] In

summer 1918, soon after Lilya and Vladimir starred in the film Encased in a Film (only fragments of which survived),

Mayakovsky and the Briks moved in together. In March 1919 all three came to

Moscow and in 1920 settled in a flat at the Gondrikov Lane,Taganka.[30]

In 1920 Mayakovsky had a brief romance with Lilya

Lavinskaya, an artist who also contributed to ROSTA. She gave birth to a son, Gleb-Nikita

Lavinsky (1921—1986),

later a Soviet sculptor.[31] In

1922 Lilya Brik fell in love with Alexander

Krasnoshchyokov, the head of the Soviet Prombank. This affair

resulted in the three months rift, which was to some extent reflected in the

poem About That (1923). Brik and Mayakovsky's

relationships ended in 1923, but they never parted. "Now I am free from

placards and love," he confessed in the poem called "For the

Jubilee" (1924). Still, when in 1926 Mayakovsky was granted a state-owned

flat at the Gendrikov Lane in Moscow, all three of them moved in and lived

there until 1930, having turned the place into the LEF headquarters.[24]

Mayakovsky continued to profess his devotion to Lilya

whom he considered a family member. It was Brik who in the mid-1930s famously

addressed Stalin with a personal letter which made all the difference in the

way poet's legacy hase been treated since in the USSR. Still, she had many

detractors (among them Lyudmila Mayakovskaya, the poet's sister) who regarded

her insensitive femme-fatale and cynical manipulator, who'd never been really

interested in either Mayakovsky or his poetry.[7] "To

me, she was a kind of monster. But Mayakovsky apparently loved her that way, armed

with a whip," remembered poet Andrey Voznesensky who knew Lilya Brik personally.[30] Literary

critic and historian Viktor Shklovsky who resented what he saw as the Briks'

exploitation of Mayakovsky both when he lived and after his death, once called

them "a family of corpse-mongers."[29]

In summer 1925 Mayakovsky traveled to New York, where he

met Russian émigré Elli Jones, born Yelizaveta Petrovna Zibert, an interpreter

who spoke Russian, French, German and English fluently. They fell in love, for

three months were inseparable, but decided to keep their affair secret. Soon

after the poet's return to the Soviet Union, Elli gave birth to daughter Patricia.

Mayakovsky saw the girl just once, in Nice,

France, in 1928, when she was three.[11]

Tatyana Yakovleva

Patricia Thompson, a professor of philosophy and women's

studies at Lehman College in New York City, is the author of the book Mayakovsky in Manhattan, in

which she told the story of her parents' love affair, relying on her mother's

unpublished memoirs and their private conversations prior to her death in 1985.

Thompson traveled to Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union, looking for

her roots, was welcomed there with respect and since then started to use her

Russian name, Yelena Vladimirovna Mayakovskaya.[11]